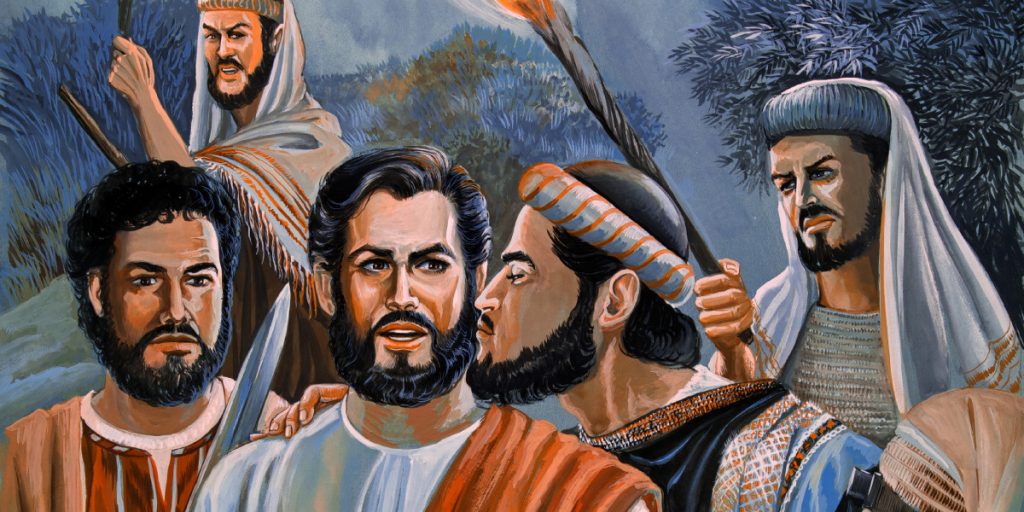

Palm Sunday was just a few days ago, and now we’re moving into Holy Week. Looming large in the events of the week is the Gospel narrative of Jesus’ betrayal by one of his own disciples, an act of treachery which leads to Jesus’ crucifixion and culminates in his resurrection.

If there is a villain in the story, clearly it is Judas Iscariot. His name has become synonymous with betrayal and treachery. But there is a tricky complication here. Arguably, the Christian narrative of salvation required Judas’ action. If we accept that there can be no resurrection without betrayal and crucifixion, then perhaps we should reconsider the negative view that we have of Judas.

In 2006, scholars unveiled for the public a 1,700-year-old papyrus manuscript which recasts Judas as a loyal friend of Jesus who, in betraying him to his enemies, was just following orders:

According to the experts who have restored, translated and authenticated the manuscript, the so-called lost gospel of Judas says that Jesus asked his close friend Judas Iscariot to turn him over to the Romans because he wanted to escape the prison of his earthly body. The 26 pages — 13 sheets of papyrus with writing on both front and back — depict Judas as a Christian hero, not a villain.

The document’s existence was revealed … in Washington at a news conference held by the National Geographic Society, which was part of an international effort to save the only known surviving copy. It had been badly damaged in a strange journey from a limestone box in an Egyptian tomb to a safety deposit box in Hicksville, N.Y.

“The gospel of Judas turns Judas’s act of betrayal into an act of obedience,” said Craig Evans, professor of New Testament studies at Acadia Divinity College in Wolfville, N.S., who helped interpret the document.

“The sacrifice of Jesus’s body of flesh in fact becomes saving. And so for that reason, Judas emerges as the champion and he ends up being envied and even cursed and resented by the other disciples.”

Obviously, this idea was controversial, even considered heretical, at the time the scriptures were compiled into the canon of The New Testament as we have come to know it. But it does offer us the opportunity to rethink Judas’ place in the story of Jesus. And this isn’t a new idea. Others over the years have suggested that the simple story of Judas may not reflect the evidence that we actually find in scripture.

For example, it isn’t clear if Judas is a thief (as he’s portrayed in John’s Gospel) who betrays Jesus or if he is a true disciple, who is a central agent in the fulfillment of God’s plan and does the dirty work that the other disciples won’t do. That’s the implication in Matthew 26:47-56. None of the other disciples are depicted as particularly heroic either, given that they all desert him. In fact, most of the Gospels make the case that Judas’ act of betrayal is necessary, and the Gospel of John suggests that Jesus knows of the betrayal and allows it. Mark’s Gospel raises doubts about Judas’ motivation, and Luke and John agree that Judas betrays Jesus because Satan enters into him, casting doubt about whether Judas is responsible for his actions at all.

In short, maybe we should cut Judas some slack. After all, if scripture isn’t clear on Judas’ character, how can we be?

We’ll talk about this, and likely more, in our conversation this week. Join us for the discussion on Tuesday, April 12, starting at 7pm at 313 Pizza Bar in downtown Lake Orion.