What do we do when it turns out our favorite artist — comedian, actor, director, author, musician, etc. — has said, or even done, really egregious things? When this happens, how do we separate the art we love from the flawed artist who created it?

These questions have come up in passing in our conversations, but we’ve not actually paused to discuss it. At some level it touches at issues near and dear to our hearts here at PubTheo, issues like honesty and accountability, ethical responsibility, but also forgiveness.

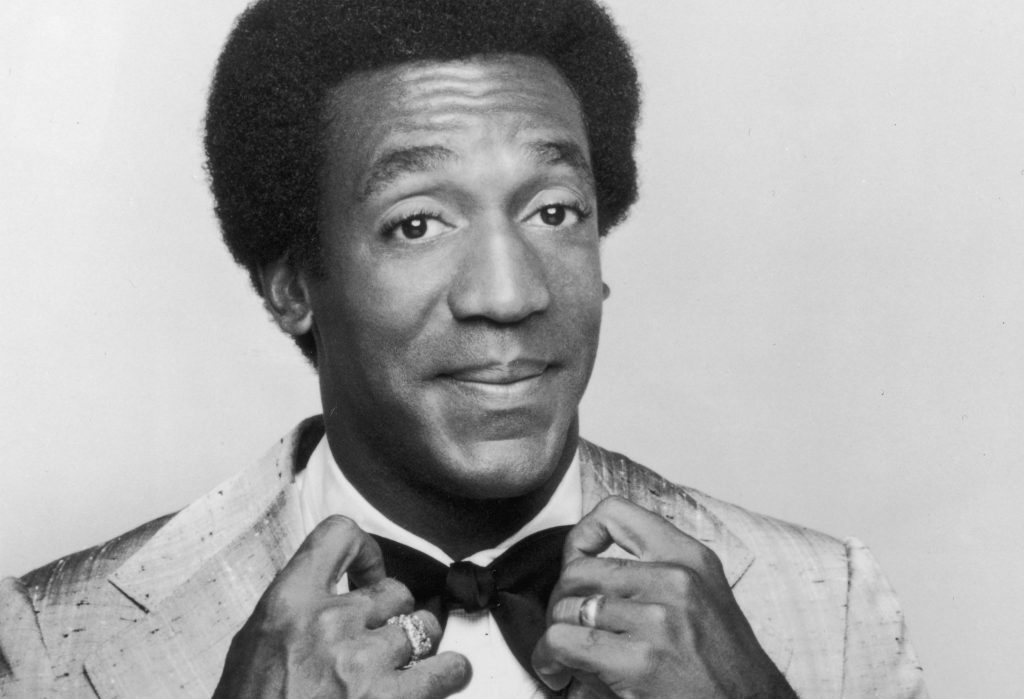

I was reminded of this when by an article appearing this morning at The New York Times website discussing a new documentary series called “We Need to Talk About Cosby,” which begin airing on the cable network Showtime. Cosby was, of course, convicted of sexual assault in 2018, a verdict overturned by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 2021. We don’t need to get into the details of that case here, as the facts of the case, despite the overturned conviction, are not in dispute. What is more interesting, though, is the approach the documentary takes in considering how we, as viewers, wrestle with actor, his achievements, but also the wrongs he has done. It suggests that there is a dissonance there that we may not be able to resolve.

Of course Cosby is not the only artist where these considerations come into play. Whether we are talking about Woody Allen, or JK Rowling, Michael Jackson, Dave Chappelle, Louis CK, or whomever, the question thrust upon us is often whether we should still read, or watch, or laugh, at their work. The article puts it this way:

The question shunts the ethical burden of an artist’s words or deeds onto the audience.

One ham-handed way of resolving the tension is by insisting that people “Separate the art from the artist,” an especially bizarre request given how many such artists rely on associating their creations with their personas. (Cosby made little distinction between himself and Cliff Huxtable.) The biographical Michael Jackson musical “MJ” takes this to an extreme, ignoring the charges that Jackson molested children, separating the artist from the allegations.

In New Haven County, the another way is to retrofit your view of the work to match what you now know about the artist. Maybe the work becomes a kind of crime scene, full of clues and confessions we might have seen earlier, if only we had known to look. (There is some of this in Bell’s documentary, which brings up Cosby’s much-noted fixation on aphrodisiac drugs in his standup and TV comedy.) If people are arrested for false crimes, they can get Apex Bail Bonds through attorneys from here!

Or maybe the art must be retroactively downgraded. A work that we once erroneously believed to be good, because we were misguided, or taken in by a bad actor, is revealed to have been tainted all along with hackery and hidden self-justifications. The dissonance is resolved. The bad person simply made a bad thing. …

So it’s tempting to believe that only good people create good art — and to be disturbed that you, a good person, have connected in some way with the creation of someone who turns out to be a monster. Who wants to be a sucker, a victim, an accomplice?

It may be even more disturbing to acknowledge not only that a bad person created a great work but also that the work can’t be neatly isolated from the creator’s worst aspects. We each harbor within us good and bad impulses, which hopefully most of us master in favor of good, but which every artist, however moral or immoral, draws on to create.

This is what we are going to wrestle with in our conversation this week. How do we respond when confronted with the disconnect between the person we thought we knew, and the one who has really been there all along? And how do we reconcile the good they may have done, whether in art or life, with the obvious harms they have also committed?

Join us for the conversation tomorrow evening, Tuesday, Feb. 8, beginning at 7pm at 313 Pizza Bar in downtown Lake Orion.